Reposted from InDaily.

A more than $400 million plan from Greenhill Energy will divert up to 200,000 tonnes of waste per year from Australian landfills according to managing director Nicholas Mumford, who has big ideas for his Adelaide-based firm.

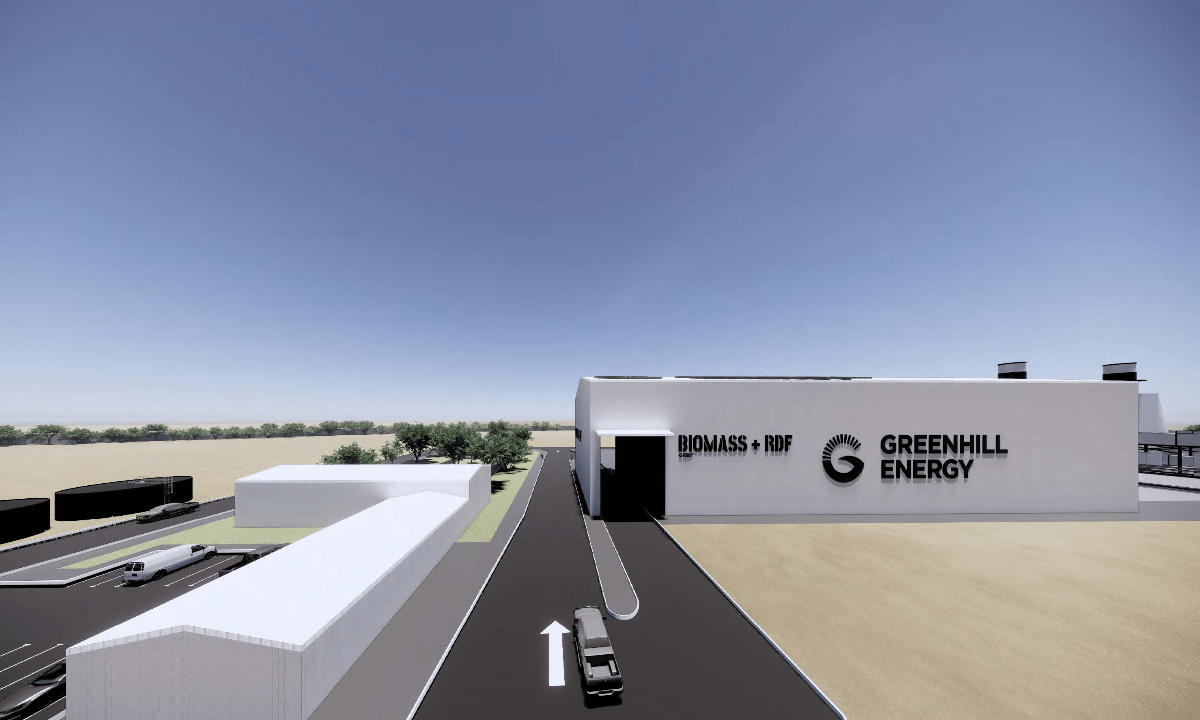

A render of Greenhill Energy’s proposed centre at Tailem Bend. Photo: Supplied.

With nine years at Santos under his belt and further experience at energy giant Shell, Nicholas Mumford is well-acquainted with the energy sector.

It was this time at Santos and Shell – the latter being one of the world’s biggest polluters – that inspired his work at Adelaide energy company Greenhill Energy.

The firm, based at Burnside, announced last year it would construct a $425 million integrated waste-to-hydrogen processing plant at Tailem Bend, south-east of Adelaide.

There the company will be able to divert up to 200,000 tonnes of waste from landfill once the facility is at full capacity, reducing greenhouse gas emissions in turn.

The Riverbend Energy Hub will turn waste and biomass into high-value products like fertilisers and synthetic fuels, and will also produce low-cost clean hydrogen for use in emission-free power and transport.

Speaking to InDaily, the managing director – who co-founded the business alongside chief technical officer Dr John Thomas – said his journey to starting Greenhill Energy was inspired by wanting to “address the broader climate change and emission reductions” issues.

“One of the drivers was to get out into the bigger wider world to be able to affect change quicker and more radically than I could sitting in a large corporate,” he said.

His decision to focus on hydrogen was made to avoid going for the “low-hanging fruit” like solar, and he was excited by hydrogen’s potential as a fuel source.

Greenhill Energy founder Nicholas Mumford. Photo: Supplied.

“Hydrogen is the jack of all trades, but it’s not the silver bullet for everything,” he said.

“Over the years hydrogen has been underutilised as a solution, simply because it’s been cost-prohibitive. I come from an oil and gas background and in many ways, hydrogen is very similar to oil and gas: it runs through pipelines, you have a similar set of standards for safety and hazard identification and so forth.

“A lot of the process, skills and background for oil and gas applies to the hydrogen sector. If we’re thinking about jobs into the future, a lot of the industry, the suppliers, the individuals that are in the oil and gas sector now in Australia and globally, for them to transition into a hydrogen-led economy in an emission-free sector then that transition is not a massive step.”

At the centre of Greenhill Energy’s plans is a $425 million integrated waste-to-hydrogen processing facility at Tailem Bend.

Once finished, it will be the first of its kind in Australia able to convert landfill waste and sustainable biomass into other products and clean hydrogen for use in power and transport.

The facility will sit on 20 hectares of land and should be fully operational within five years from now. Once at full capacity, it is expected to be able to manufacture more than 100,000 tonnes of urea fertilisers.

The project has State Government crown sponsorship, and, pending approvals, in 2025 the company will have constructed a singular gasifier that will be able to process 60,000 tonnes of waste per year – equivalent to about 1500 fully loaded semi-trailer trucks.

The company estimates about 300 jobs will be created during construction and once completed about 50 to 100 direct jobs.

In March, the company announced it had partnered with the City of West Torrens, Solo Resource Recovery and Peats Soil and Garden Supplies to establish a demonstration pilot program.

That demo will see the pre-processing of waste at the Adelaide Waste & Recycling Centre at North Plympton, followed by the processing of material to produce syngas using the University of Adelaide’s existing gasification facilities at its Thebarton campus.

A render of Greenhill Energy’s proposed project. Photo: Supplied.

“This partnership was formed with a broader vision to build an industrial scale facility to convert landfill waste into high-value products, such as clean hydrogen,” Mumford said at the time.

“This process will effectively mature Australia’s circular economy and contribute to considerable emission reductions in Australia’s waste sector.”

According to the International Energy Agency, methane is responsible for about 30 per cent of the rise in global temperatures post-industrial revolution.

“It’s a massive issue across the globe,” he said.

“We need to reduce our emissions a lot quicker than what we’re doing globally to hit our net zero targets, and we need to target the industries that have the biggest bang for your buck for the biggest impact.

“By diverting waste away from landfill, you’re not producing methane emissions. You put it through a process that does have a level of CO2 emission, but those CO2 emissions are utilised in an end-to-end process because we’re manufacturing products – higher-value products – from the material.”

He said his process “ticks a lot of boxes” in one go, “and provides jobs for the local community as well”.

The process he’s using has been adopted internationally, he said, but the urea fertiliser component of Greenhill’s project is “unique”.

“The downstream technology for urea is very conventional once you have the hydrogen and CO2 – that’s been done countless times globally – but taking the process through the whole end-to-end is a bit unique,” he said.

“What we’re trying to do is really uplift the value and upcycle the landfill waste into something of higher value so that we can actually start diverting away from landfill at a large scale.”

Further, there’s a “big opportunity internationally” too for Greenhill Energy which has a patent pending for its technology.

“We’re looking to leverage the technology internationally in due course, and we’re also looking at multiple facilities around Australia,” he said.

“There’s a really big opportunity internationally with what we’re talking about here. There’s 1.6 billion people in the world that don’t have electricity for example, and there’s a lot of waste that sits around the world and stockpiled in some of the countries that probably have very little net wealth.